Censorship has increased a lot during the last decade

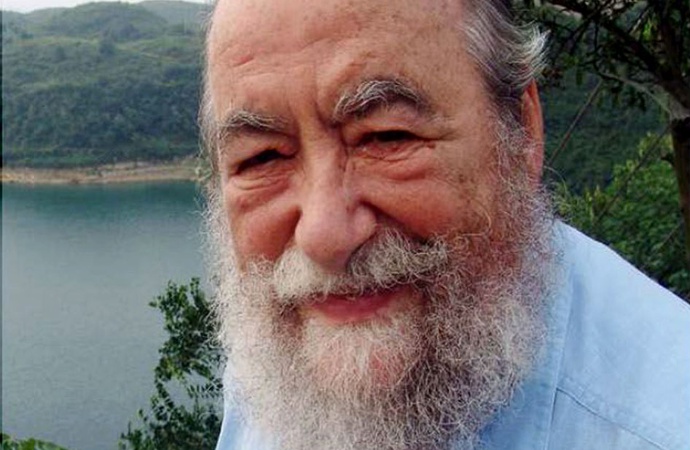

On this occasion I have the privilege of speaking with one of the most important scholars of humor in the world, Professor John A. Lent.

I had the pleasure of meeting him at the Boston Festival 2010, United States, where he was the president of the jury for the graphic humor contest and I was the jury for the literary humor contest.

When I found out that I would share with him, I began to investigate his career and was pleasantly surprised at what he has achieved in the field of humor, especially in cartooning (graphic humor).

I remember that on one of the Festival's Boston nights, I had the opportunity to present a couple of numbers by our group La Seña del Humor on stage, together with my colleague, Aramis Quintero (also a member of the jury) and at the end John Lent, with his very pleasant wife, came over to congratulate us and when we asked him if he had understood, since we did it in Spanish, a language he did not speak, he told us that he had understood all the jokes from start to finish and had laughed a lot. That's where my admiration grew, for being such an intelligent, open and insightful person.

Since then we have been in contact by e-mail.

I am also pleased to mention that a few years later, when I discovered that I could make humorous photomontages, he was one of the first I asked if it was worth it or not for me to continue doing them, sending him my first works. He immediately replied kindly that the photomontages were great, that it was a novel way of making humor and that he had to continue making them. Of course I listened to him and that modality has given me great satisfaction.

In short, I am a fanatical admirer of this great student of humor and therefore it is an honor and a pleasure, I repeat, to talk with him now.

But what could I say about him to introduce him? Only he's a professor emeritus at Temple University. That he has been a pioneer in teaching and research during his sixty-year career in the fields of mass communication and popular culture in Asia and the Caribbean, comics and animation, and communication for development. That he is the author or editor of eighty-five books, that he started and edited three magazines, including the International Journal of Comic Art, and that he founded at least six international academic associations and the first university school of communication in Malaysia.

However, all that seems to me little, insufficient, to introduce John A. Lent (JAL from now on), so…

PP: Master, to begin with, could you introduce yourself -professionally speaking-, in case any humorsapiens.com reader doesn't know you?

JAL: Thank you, Pepe, for such a kind introduction, especially coming from a distinguished humorist and researcher of humor such as you are. Your first mistake: You don't ask a teacher who spent more than 50 years in the classroom to talk about himself. That could go on for days.

I will try to be brief. I trained in journalism with the hope of one day being a foreign correspondent. I had no intention of continuing my education, but I did intend to accept one of the offers to be a sports editor. That was in 1958. So, I heard from my selective service board (a misnomer actually) that I was going to be drafted into the army. I wasted no time getting into graduate school. After completing my master's degree, I was offered a low-paying position (what else?) to teach "dumb" (remedial) English and be the publicist at a small college in West Virginia. There, I got married, the first of three weddings (Was I a slow learner? Or did I try to marry well, with practice?) I've had.

From there, I was awarded a scholarship to pursue a Ph.D. at Syracuse University; I finished all the coursework, but I ruffled the dean's pens by writing a critical book about the school's financial backer. My next step was the Philippines, where I was awarded a one-year Fulbright scholarship and developed a keen interest in Asian media.

From 1965 to 1970, I moved from one teaching job to another (four different universities), took an active role in fighting the Vietnam War, civil rights, and other causes, and had the opportunity to use an e-line. me. Cumming's poem, "There's Some Shit I Can't Eat," in two resignation letters. I finished a "renewed" Ph.D. at the University of Iowa, after which I accepted a position at Universiti Sains Malaysia, developing the first mass communication degree program in Malaysia.

Did I say this was going to be short?

PP: Ha ha… I think it was. At least I wasn't bored, on the contrary, I was like I was listening to a very entertaining story. Thank you John. And now getting into the matter, what is the definition of humor that pleases you the most?

JAL: Defining humor is not an easy task. Perhaps humor is an action or verbal retort that, intentionally or by chance, evokes laughter, joy, and thoughtfulness. It can consist of parody, satire, humor, sarcasm, eroticism, wit, various linguistic devices, traps, jokes, the follies of everyday life, ridicule, exaggeration.

PP: Yes, defining humor is not an easy task. But I think you have to try, don't you? Well, I continue. And now on a topic that is in fashion: does humor have limits? Do you think censorship has increased lately? Do you think that the field to do humor is being reduced, due to the tyranny of the politically correct?

JAL: I think there are limits to humor, although I am a strong advocate of freedom of expression. For example, making a joke and falsely yelling "Fire!" in a crowded space where people can get trampled is irresponsible. The Danish newspaper and the Charlie Hebdo cartoons mocking the Prophet were irresponsible; the publishers and artists intended to provoke the Islamic community, knowing full well that there would be protests that could lead to injuries and deaths. Just because you can do something doesn't mean you should. There are so many other issues and individuals that should be prodded; Why choose a religious leader who died a long time ago and is not in the news?

Censorship has increased a lot during the last decade, strengthened by a string of authoritarian leaders: Trump, Xi Jinping, Duterte, Putin, Marcos, Bolsonaro, etc.; conglomerates that own large chunks of the media and entertainment industries that they often use to protect their vested interests; the concept of "guided cartoon" (my coinage), where cartoons and humor are guided by the authorities with the false promise that this will strengthen national development, and what many cartoonists told me was the worst control mechanism: self-censorship.

Other obstacles to the practice of humor are the declining number of political cartoonists, the reduction of newspaper comic strips from huge panels with elaborate backgrounds and entertaining dialogue to postage-stamp-sized drawings devoid of what actually made the strips. comedies, and stand-up comedy. that without the use of the words "fuck" and "son of a bitch", it would fail. Don't get me wrong; I have no problem with those words; it's just that they often make up for the lack of a joke. I am also annoyed by the "canned laughter" on radio and television, which often leaves one stumped as to what is funny.

Finally, there is political correctness gone wrong. We have taken a good concept and tarnished it. So much is off limits that sometimes I think we've become a humorless society. Some actions are particularly ridiculous, like taking famous political cartoonist Thomas Nast's name from a prestigious award, because he skewered Catholics more than a century earlier. Removing from view or destroying early American cartoon figures because they denigrated ethnic groups is questionable; if they are destroyed so is the proof that they ever existed. In some quarters, even questioning these actions, as I am doing now, raises undeserved charges of bigotry.

PP: I totally agree with you, Master. But let's get into the theory a bit. For you, what are the formal differences between the concepts “cartoon”, “editorial humor or editorial cartoon”, “comic” (the humorous comic) and “comic strips” (the humorous one, of course)? I ask because we have different nuances in Spanish.

JAL: To me, "cartoon" is an umbrella term that can be applied to all other concepts, whether it's an editorial, a joke, a comic, a comic strip, or a film cartoon. However, it is usually applicable to editorials, gags and films. Editorial or political cartoons usually take a position: of the artist, the editor or the editor; gag is usually a stand-alone panel cartoon intended to elicit laughs (the New Yorker, for example); the comic strip is usually four panels with an introduction, action, and resolution, published in newspapers and some magazines, and often syndicated; and comics refers to comics, although they are actually magazines. These vary in size in Europe, Japan, Korea, etc.

PP: I'm sure we agree with those formalities all over the planet, but the language confuses things. Another example: can the "caricature", the one where the drawing exaggerates the features of a person, be considered as a modality within cartooning?

JAL: Definitively, the caricature is a modality in the vignette. It has users in all branches of cartooning: definitely editorial cartooning, as well as to a more limited degree comics and cartoons. Caricature (karikatur) has different meanings in other regions.

PP: I have always had the following doubt, Master: humorous drawing being more difficult to master as a human skill than photography, why are there fewer humorous photographers and fewer humorous photomontagers than cartoonists?

JAL: I have always liked humorous photography and at another time, fotonovelas as once popular in Latin America. A South African cartoonist friend of mine still does photocomics, but as you say, they are much rarer. I don't know why humorous photography isn't as popular as humorous cartoons, but I'll venture a few guesses: no one has found a successful way to market them; they may not allow the same degree of exaggeration as drawings; they may require more time and effort, needing to come up with an idea, find individuals to be subjects and get their permission to do so, and organize the event. These are just guesses.

PP: But you may be right. And another conjecture would be that this modality is more expensive, compared to what is needed to make a drawing, I say. Now, Master, what can you say to those who think that cartooning is a minor art?

JAL: First of all, I am grateful that caricature is finally considered an art. For years, it was considered less of an art, not worthy of being taken seriously, preserved, or studied. I remember a time when the media and the general population made fun of all popular culture, including cartoons. I think we no longer have to justify drawing or studying cartoons. In that sense we have arrived professionally and academically. In some parts of the world (parts of the southern hemispheres), cartoonists still tell me that they are denied respect and recognition by the authorities and the public.

I also believe that the prominent demarcation between high and low art is not as rigid as it used to be, as some older critics have realized that forms of popular art considered classical or high today were popular and mass-oriented in another time (eg opera, Shakespeare), or, Having seen the constant professionalization and glorification of cartoons, they have decided to get off their high horses.

I would argue that caricature has become a major art with its share of achievements worthy of such distinction: recognition by massively funded governments (China, Korea) and honors (recent "knighthood" of Seth and Zapiro, honorific of datuk for Latin) ; important exhibitions around the world, museums of the highest quality (Japan, Korea, Poland, Belgium, France, etc.) and an avalanche of books and periodicals that is difficult to follow.

PP: Humor in general has always been underrated. One more foolishness of the human being. Now, dear John, we know that you are an expert in Chinese and Eastern cartooning in general, so I ask you: what would be the biggest differences with Western cartooning?

JAL: It is not easy to answer this, because Asia is a great variety of cultures and languages. You almost have to answer this question with country-specific examples. But let me try. Political cartoons in almost every Asian country have either dried up or been non-existent for eons. What little is left is "guided cartoon" or "government cartoon" and cartoon under chaebol (big conglomerate) controlled media. A few countries are in better shape than others (perhaps India, the Philippines). An extremely low number of Asian newspapers carry comic strips, and typically the few that do appear are US syndicated strips. Comics vary; some have hundreds of pages, such as in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan; The Philippines and India have American-style comics. Previously, China had the tiny “lianhuanhua”, palm-sized illustrated books with one image per page. Vertical scrolling “Webtoons”, first started in South Korea, are growing rapidly.

We must remember that almost all of Asia had been colonized by European countries and the US, and while many had histories of highly exaggerated, humorous, satirical art found in millennia-old murals and grave markings, caricatures as they are known arrived. today. With the colonists, for example, humorous periodicals (the various descendants of Punch or Puck in Japan, China, India, etc.) and politically oriented independent cartoons.

PP: Fascinating that story. If life were longer I'd love to investigate all that, like you. And by the way, could you tell us about the current situation of cartooning in the world? And specifically about the health of cartooning in the Portuguese-Hispanic world, the origin of most humorsapien.com readers?

JAL: The cartoon world is richly furnished, if not always well fed. In my travels, I have met and interviewed hundreds and hundreds of cartoonists of all kinds. They have been the most accommodating and, in most cases, humorous interviewees, despite their struggle to put rice on the table. Most have day jobs, ranging from betel nut vendor and ferry captain, to doctor, psychiatrist and architect.

I believe that the health of the cartoon is stable in the Latin American countries that I know, which are Cuba, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia. Most cartoonists have jobs; some are world famous (Ares, Mordillo, Quino), and others regularly receive top prizes at international festivals. Brazil has one of the first university courses in comic art in the world; there are caricature museums (as in San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba); famous comic contests survive (Calicomix in Colombia); many books and newspapers related to Latin American comics appear at least in Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Chile, Cuba and Colombia; and a few hard-hitting political cartoonists manage to withstand continued repression (Bonil and Vargas in Ecuador; Rayma formerly in Venezuela).

PP: Yes, I know them, many of them are friends of mine and what they have been through is terrible. It is not easy to be a cartoonist, especially a politician. In addition, another problem: every time the creators of cartooning have fewer spaces to publish, since magazines, weeklies, etc. are closed. So logic indicates that the Internet is going to solve this problem. However, there is a serious conflict that still -for the most part-, the works published there are not remunerated. How do you see the future of cartooning then?

JAL: Cartoons and comics will continue, but in different forms. Cartoons/comics are already online, usually in horizontal format, turning page by page, but since 2000, in vertical format scrolling through Webtoons. Remuneration remains an issue, although remedies are being introduced through Webtoons, such as authors sharing ad revenue and being paid up front by web platforms. Although not many, some Korean webtoonists make millions of dollars a year.

The pay problem will be solved, and cartoons will become even more paperless and, I think, more textless, as cartoons become even more minuscule (to fit on a so-called "smart" phone) and audiences become more illiterate and even illiterate.

PP: Very good. Although now I change a little twist. Teacher, a large part of your life has been dedicated to teaching in different educational establishments, universities, etc., for that reason I would like to ask you a question that is often asked of me: can humor be taught? How has your experience as a teacher in this subject been?

JAL: I have not taught humor; I have taught about humor through cartoons. I don't think humor can be taught; humor is learned by observing, reading, associating with humorous and humorless people. Humor comes out of your environment. My concept of humor will probably be different from yours. I come from a poor background, living in a fatalistic type of community (where the thought was that your ancestors were coal miners, so you are destined to be a miner). The humor was often harsh, consisting of bullying, mockery, and ethnic slurs ("you're a dago"); some were endemic to the region; some came from outside through comic strips or people who had traveled to a nearby city. Bearing this background, I think I'm not as sensitive to criticism or insults as others, I can take and give put-downs, I'm quick on the draw, able to think of a joke or a funny line almost instantly. Perhaps my sense of humor is similar to the soccer formula: a good attack is a good defense.

The comic art courses I taught, as far back as the 1980s, dealt with the background and issues primarily of non-American comics, animation, and political cartoons. My goal was to broaden the perspectives of students, a difficult task that I don't think I could achieve, and so I retired, but at 75 years old.

PP: I will give you my opinion, Master, in other words, since I know that we agree. I think one could learn the language, the techniques, of humor as an art. But it is something very limited, unfortunately. Because if students do not have the capacity for imagination, do not have the gift of creativity, if they do not have a stimulated and developed sense of humor, what is the use of learning that language? And those shortcomings are not taught, of course. Although we can make students aware of how necessary and fundamental it is to develop all of this. So you need to go to college to create humor? Of course not, because the basis of most of these shortcomings mentioned is of a cultural nature. Everything can be developed with readings, for example; with wanting to know, with browsing, with questioning everything, with traveling, learning more about each art and consuming it more, with paying more attention to what is seen, heard and what happens in life, etcetera, etcetera. Anyway, I realized that I extended too much, and therefore I return to our "dialogue" right away. So to refresh so much theory, could you tell us an anecdote (or more than one), funny, ingenious or curious, related to your work in humor, whether researching, studying, teaching, or interacting with comedians?

JAL: Let me go back to the 1940s when I was a fifth grader and aspired to be a cartoonist. I copied comics from the Sunday supplement, "Puck," of the Pittsburgh Press, a newspaper owned by Hearst. The supplement's logo was made with a drawing of Puck and, if I remember correctly, the words "How foolish are these mortals." My mom saw my acting (she saw it all), she thought the "P" was an "F" and I "retired" from cartooning immediately after. She also pushed me to turn the tide on the high caliber of cartoonists in the 1940s; He knew he couldn't compete with masters like Burne Hogarth, George McManus, Hal Foster, or Alex Raymond.

My interactions with the cartoonists were full of funny and/or unusual incidents. Especially entertaining were the anecdotes associated with Cuban artists. Being in Havana in 1991, a time of scarcity due to the collapse of the Soviet Union, I wanted to talk to the cartoonist Ajubel. I left a message in his mailbox at the writers center, unaware that Ajubel had moved to Spain. The note was "intercepted" by cartoonists Lillo and Alba, who called me and asked if they could meet me at my hotel, which was off-limits to Cubans at the time. I invited them to have a beer with me; they each ordered two and a pack of cigarettes, and they continued to do so for a few hours. Finally, exasperated, I asked when we were going to start the interview. It was close to midnight. Lillo suggested that he order a case of beer and lots of cigarettes and walk to his nearby house. Although it was early in the morning, his wife received us warmly and Lillo, Alba and I chatted for a long time afterwards.

It was on this research trip that I saw the ingenuity of the Cubans. Animator Juan Padrón showed me an animation camera from the 1920s that they still use after recovering it from a plane crash decades earlier; Tomy told how his familiarity with the roots and juices of plants allowed him to continue painting when paints were scarce; Manuel presented me with a large ceramic plate with a cartoon character on its face that was his way of continuing to draw during a severe paper shortage, and Ángel Boligan, who was just entering his teens, explained how he provided a place for his colleagues in San Antonio de los Baños by publishing his caricatures in a newspaper format in a local pharmacy.

There were plenty of other memorable experiences, including hanging out with the famous Ralph Steadman and his wife, Anna, for a week in Turkey; trying to find a moment, at a festival in Lviv, when a group of cartoonists from Eastern Europe would be sober enough to be interviewed; being the guest at the annual "potato" party of literary and artistic stalwarts in Kathmandu; join Filipino political cartoonist Nonoy Marcelo at his usual breakfast at 10 p.m. m.; losing a "belly bounce" match against a great cartoonist in Poland, and spending considerable time with cartoon giants, such as Jerry Robinson, Lat, Abu Abraham, R. K. Laxman, Terry Mosher, Fang Cheng, Pran, Oleg Dergachov, Gado and Anton Kannemeyer.

PP: Spectacular! What envy! Thank you John. Well, what is the project, in terms of humor, that you still have to do because you have never been able to carry it out and have always wanted to do it?

JAL: I always have pending projects, which keeps my energy level high. I want to keep the International Journal of Comic Art, which I founded and have published and edited twice a year since 1999, almost all of the work done at home. I have two books coming out in the next six months: one on Asian political cartoons; the other, transnationalism and comics in Asia. I will finish a book on Korean cartoons by September and start others on Caribbean cartoons and erotic cartoons worldwide or limited to Asia.

PP: I love to see you with so many projects and so much energy... Teacher, I always close my interviews in this way: is there a question that I didn't ask you and that you would have liked me to ask? And if so, could you answer it now?

JAL: Maybe you could have asked me, how do I work? And I would have answered you: I am a very organized person, I plan my work schedule so that it is carried out by year, quarter, week and day. I record my work hours on a piece of paper, indicating what I did, by day and week; basically, i'm my own clock in. It gives me a sense of accomplishment to mark what I have completed. My goal, which I almost always meet, is to work between 40 and 50 hours a week. I work much better in a quiet environment and I think those who claim to multitask are talking nonsense. Research has shown that multitasking results in poor quality workmanship. I don't lean towards technology, but I consider it just another tool. Everything I write is done in pen on notepads, and I think I can feel a stream of ideas and words flowing from my brain to my fingertips.

It may all seem over the top, obsessive behavior, but it works for me.

PP: Great! Great information. Thank you very much, Master.

JAL: Thanks to you, Pepe, for encouraging me to refresh and remember these pleasant moments.

PP: I am the one who is grateful for having dedicated your time and effort to answer my questions. I wish you good health and much success, because I know that you will continue to give your valuable work to Humanity.